Simon Winchester’s Exactly offers a grounded way of understanding the Industrial Revolution that is largely absent from standard accounts. Rather than celebrating steam as a symbol of power or progress, or romanticising the lives of inventors, Winchester directs attention to the precise and often invisible engineering work that made industrialisation possible. His focus is on measurability, repeatability, and the relentless reduction of variance so that machines could operate reliably in real-world conditions.

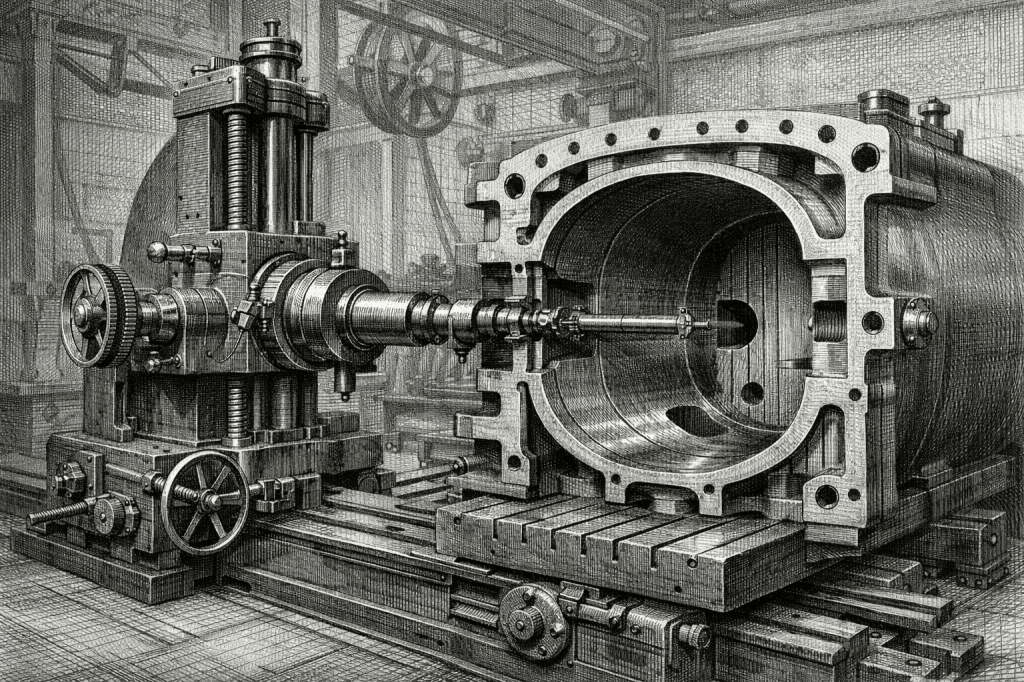

The book’s central insight is deceptively simple. Industrial modernity emerged only when craftsmen learned how to make things exactly to specification, again and again. Producing a part that was roughly the right shape was no longer sufficient. Components had to meet narrow dimensional tolerances predictably and consistently. Once that threshold was crossed, engines worked efficiently, machines became modular, and assembly systems could scale. Winchester shifts our attention away from heroic moments of invention and towards the mechanics of precision itself.

This emphasis on measurability and repeatability provides a useful anchor for reframing the economic impact of AI today. In the early industrial era, precision meant machining a cylinder so that it was truly round. Solving that very specific geometric problem at scale unlocked the steam engine’s potential and turned theoretical thermodynamics into viable economic systems. It was not the existence of steam power that transformed economies, but the ability to harness it reliably, repeatedly, and at scale.

Winchester’s account makes clear that the Industrial Revolution did not begin with a single invention. It began with a break in variance. Once producers could guarantee that a machine part met specification every time, designers could assume consistent behaviour. Processes could be standardised, supply chains coordinated, and organisations planned around certainty rather than continual adjustment. That same structural logic underpins the current shift in AI.

When Tools Become Infrastructure

The early steam engine did not transform the economy because it was clever. It transformed the economy because it became embedded. Initially, steam engines were curiosities that pumped water from mines and demonstrated raw mechanical power. They were impressive, but isolated. Real transformation began when steam ceased to be a standalone machine and became infrastructure.

Locomotives connected cities, factories reorganised around mechanical power rather than human muscle, and supply chains lengthened. Urbanisation accelerated, capital aggregated, and management emerged as a discipline because coordination suddenly mattered more than craft. The Industrial Revolution was not ultimately about engines. It was about systems built around engines. We are now at a comparable inflection point with AI.

For the past several years, AI has followed a familiar trajectory. Models have improved rapidly, costs (of tokens) are falling, and capabilities accumulating.

What was novel in the beginning has become routine. Generating content, writing code, creating new images, reasoning, multimodal input, and tool use.

This phase closely resembles early steam: raw capability advancing at visible speed. Yet capability alone does not restructure an economy.

Most organisations still treat AI as a cognitive assistant. It drafts documents, summarises material, generates ideas, speeds up coding, and improves productivity at the margin. This is equivalent to bolting a steam engine onto a single machine in a workshop. It is useful, but not transformative. The shift now underway is different. AI systems are beginning to plan, coordinate, execute, verify, and iterate across entire workflows. They are not merely assisting humans but completing structured outcomes.

This marks the move from tool to infrastructure.

The locomotive did not matter because it moved faster than a horse. It mattered because it standardised movement. Railways created timetables, which required synchronisation. Synchronisation demanded standards, and standards enabled scale. Scale, in turn, reshaped geography. When transport became reliable, labour markets expanded, cities grew, and specialisation deepened. New institutions such as insurance, logistics firms, and modern finance emerged to manage the resulting complexity. The second‑order effects far outweighed the original invention.

The Geometry of Agentic Work

Agentic AI exhibits similar properties. When systems can reliably decompose goals into tasks, allocate work to sub‑agents, call tools, validate outputs, and escalate exceptions, execution becomes programmable. Work becomes modular, and coordination can be automated. This changes organisational geometry. If execution capacity scales independently of headcount, constraints shift. Management layers thin, decision velocity increases, and firm boundaries become more fluid. Specialised micro‑firms can compete with incumbents because coordination costs collapse. The real disruption is not smarter chat, but cheaper coordination.

In the early industrial era, power was the binding constraint. Once steam addressed that, the bottleneck shifted to organisation: factory layout, labour discipline, supply‑chain reliability, and capital allocation. We are observing the same pattern today. The constraint is no longer model intelligence, but workflow design. Most enterprises remain structured around human hand‑offs, tacit knowledge, and exception management. Layering AI onto these structures yields incremental gains at best. Structural gains require structural change.

To compound, outcomes must be clearly defined, processes explicitly mapped, and decision rights made visible. Verification loops need to be built in rather than retrofitted. Without these conditions, agentic systems stall. This explains why many pilots fail. The model works, but the organisation does not.

Railways did not merely move goods; they concentrated people. Cities expanded because proximity amplified productivity through dense networks of talent, capital, and infrastructure. AI will produce its own form of digital urbanisation. This will not be geographic, but organisational. Firms that successfully redesign around agentic systems will compound faster, iterate more quickly, absorb shocks more effectively, and experiment continuously. Lagging organisations will appear functional but slow, much like towns bypassed by the rail network. The divergence will be structural rather than gradual.

Industrialisation did not eliminate labour; it reconfigured it. Craft gave way to factory work, which later gave way to managerial and technical roles. Over time, entirely new professions emerged. The same pattern is emerging. As execution shifts towards machines, supervision, governance, exception handling, system design, and strategic judgement increase in value. Judgement does not disappear; it becomes more leveraged. Framing the future as a choice between full automation and unchanged employment misses the historical lesson, which points instead to large‑scale role redefinition.

Crossing the Structural Threshold

For AI to mirror the Industrial Revolution, several conditions must hold. Agentic systems must become reliable enough for repeated execution, not just impressive demonstrations. Standards must emerge for interoperability, governance, evaluation, and security, much as rail required common gauges and time standards. Capital must move from experimentation to integration, and leaders must redesign operating models rather than merely deploy tools. Most importantly, organisations must recognise that coordination, not intelligence, is the primary economic lever.

Steam initially assisted human labour before it reorganised society. AI now sits at that same boundary. The next phase is not about models that answer better questions, but about systems that execute reliably. When AI is embedded into the fabric of workflows, spanning planning, action, verification, and learning, productivity will no longer be measured in prompts per employee. It will be measured in outcomes per system. That is when assistance becomes execution, and execution becomes structural change.